By COREY LEVITAN

My trembling right foot slips off the rung as I descend the ladder backward. The ground, where so many of my fondest memories have occurred, lies 921 feet straight down.

I don’t want to say I’m afraid of heights, but I talk to God whenever the ski lift goes over those roller things. Yet here I am, hanging outside the observation tower at the Stratosphere, washing the windows. Yes, the ones at the tippy top.

And I’ve lost my footing. My ass is glass.

When I report for work at 6 a.m., I’m warned that sneakers aren’t appropriate footwear. But this crew goes up only once every three months, and I don’t want to miss the chance.

There’s no better place than the Stratosphere to launch a series of Las Vegas adventures. The tallest structure west of the Mississippi, this giant monument to the modern air traffic control tower has become the city’s architectural emblem. Visible from everywhere in the valley, it’s more popular than the compass as a navigation tool. (Especially to me, since I haven’t yet figured out why U.S. 95 claims to go south while heading east.)

Once I step out onto the 109th floor observation deck, however, the idea sounds better on paper.

The Stratosphere isn’t in the actual stratosphere, by the way. That doesn’t begin until 10 miles up. But I suppose the Lower Troposphere Hotel & Casino doesn’t have quite the same ring.

Anyway, the misnomer is fine by me today, because the actual stratosphere contains less than 0.01 percent of the earth’s breathable air, and I’m hyperventilating as it is.

If you view the Stratosphere from the correct side, you can make out a thin metallic band stretching from the top to the bottom of the crown, like the tuning indicator on a transistor radio. That’s the window-washing rig, a metal cage about 4 feet wide and seven stories long. (A horizontal scaffold won’t work because the Stratosphere’s windows curve inward as they drop.)

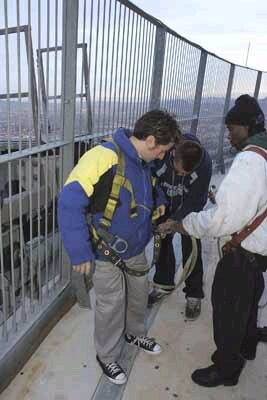

There is no direct access to this rig, I’m disturbed to discover. Window-washers must scale a 10-foot fence, the same one scaled by the three distraught individuals who committed suicide since the tower opened in 1996. On the other side of that fence waits either a tiny landing platform, or air.

Sure, I’m wearing a harness clamped to the fence. But dangling back and forth in the sky, like a wrecking ball leaking urine, is not the way I like to begin my Thursday mornings.

I aim really, really well.

“Ooh, look, IHOP!” says Trevor “T.J.” Carter, the washer below me, as he points out a building that lies a shrieking, 45-second drop below him. “I could go for some Rooty Tooty Fresh and Fruity right about now!”

I try looking up instead. It’s worse. The windows above extend outward, so taking them in requires teetering backward. Next, I try focusing on the elegantly set tables inside the Top of the World restaurant in front of me. The cost to dine here and watch the fireworks on New Year’s Eve: $350.

I would pay double that to sit there right now.

To give you a feel for how high 921 feet is, it’s 331 feet below the Empire State Building that’s not on the Strip, 276 feet above what will soon be the tallest hotel in Las Vegas, and the same height as the ego of that hotel’s owner: Donald Trump.

“I used to be scared, too,” says Carter, a 19-year-old Anaheim, Calif., transplant. “And then I looked at my first paycheck.”

Carter, who worked at M&M’s World down the Strip before a window-washing crony brought him into the business four months ago, reports earning $28 an hour.

Actually, it’s not heights that scare me so much as plunges to my death. So far, the company we’re working for, Executive Window Cleaning, which also scrubs panes at The Orleans and Riviera, hasn’t lost a soul. But two Boston window washers died in 2003 when their rigging broke. And in November, two narrowly escaped with their lives in Denver.

I’ve obviously written this article, so I’m not a new statistic. However, this information is not available to me in the moment. In fact, even the Stratosphere doesn’t consider my safety a good bet. It required a $1 million insurance policy just to let me up here. This does not serve to make me feel safer, only more frustrated, since I’m only worth that kind of money as a lethal projectile, not a stationary journalist.

“Let’s go!” shouts my other co-washer, 31-year-old Las Vegas resident Maurice Horne, who is situated above me.

We’re behind schedule because I arrived 15 minutes late, a victim of traffic.

Horne, a former telemarketer who relocated from Detroit last year, says I’m slowing things down further because of my technique. He shows me again.

First I take my mop and tie it to my wrist so it doesn’t fall and bore a hole straight to the earth’s mantle. Then I dunk it in my bucket of sudsy water and slop it on the window. Then I squeegee it dry.

“Haven’t you ever cleaned a window before?” Horne asks.

Sure I have, I tell him, in the various apartments I’ve rented. (This is not true at all. One time, a bird flew into my sliding patio door and I moved out.)

A steady stream of used suds has been leaking from Horne’s bucket all over me since we began. This isn’t so bad until Horne reveals that one of the stains he removed was vomit from an overexcited customer of Insanity — the Ride, the latest of several spinning amusement machines up top.

But the immediate problem posed by Horne’s suds is more serious: My sneakers are now as tractionless as a new downtown high-rise condo plan.

“Are you all right?” Horne calls down after he hears me slip.

My desperate clutch on the ladder supports my weight as the movie of my life flashes before my eyes. (Turns out, it’s a bad comedy starring my middle-school guidance counselor, Mr. Bashner, who warned me I would do something stupid later in life, if I didn’t “shape up.”)

A honking spot of sludge remains on the outside edge of one of my windows. My knees are now buckling too much to reach it. Horne descends to do it for me.

“These windows have to be clean whether you’re doing an article or not,” he says, annoyed but now also sympathetic. He explains that the hotel’s director and president both inspect the glass from inside.

“Hang on!” Carter shouts.

Every 15 minutes, the rig revolves, hydraulically, around to the right, to the next row of panes we’re required to wash. As it moves, it wobbles. Forget the ride up top (which I’m probably not tall enough to sample anyway.) This is Insanity — the Ride.

After 45 minutes, I’m ready to de-rig. I mean really ready. Unfortunately, window-washers are not allowed off until they make a full quarter revolution around the Stratosphere.

This takes three hours.

“Oh come on!” Carter responds to my whining. “Where else can you get a view like this?”

I inform him of a view that I know happens to be identical.

It’s from inside the top of the Stratosphere.