By COREY LEVITAN

It’s a given that we’re willing to consider sources with dubious credentials to be experts. It’s like we want to believe that Dr. Phil is a licensed psychologist and that Wikipedia isn’t compiled by crazy people.

But just how far are we willing to stretch that desire to believe in the people telling us how to eat, vote, love, raise children, and choose investments?

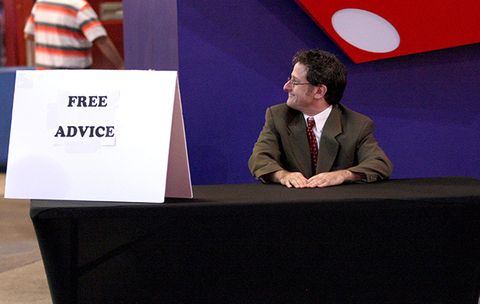

I posed as an expert recently at the Fremont Street Experience in Las Vegas, offering free advice to anyone who asked for it. What I discovered made me want to jump off a roof.

(Photo: Los Angelenos Miguel Canto, l., and Bryan Paranal ask the location of the perfect left-hand break. “Somewhere around Ventura County Line,” Free Advice Man advises, drawing on one of the lyrics he recalls from “Surfin’ USA.”)

Within 15 minutes of setting up my long table with a “FREE ADVICE” sign, I was staring at a line that was eight advice-seekers deep.

Some mistook me for an information booth: “Where do I purchase tickets to the SlotZilla zipline?”

And some were there for the entertainment value: “How do I find my friend’s penis?”

But most seemed to have serious problems they sought answers for.

Jason (not his name), a chiropractor from Minneapolis, suspected his wife of having a lesbian affair with their nanny. He said they‘ll have conversations that stop whenever he enters the room and that once, when arriving home earlier than usual, he saw them exit the master bathroom together.

Let me remind you that Jason had no problem revealing this personal information to some douchebag seated next to a “FREE ADVICE” sign. Well, I was wearing a suit, though, so there’s that.

“People are naturally dependent,” said Chicago-based psychotherapist David Klow. “We rely on others right from the start, and we regress when we are in the face of authority figures. When someone claims to be an expert, and does so convincingly, we become a time machine and regress back to times when teachers, coaches, parents, and other authorities directed us and shaped our lives.

“We sacrifice our own self-authorization.”

My advice to Jason was to gather more evidence before destroying all trust in his marriage. Then I inquired whether the nanny was hot, because if he’s going to end up in divorce court anyway, why not have a threesome before his marriage implodes?

Hey, you get what you pay for from Free Advice Man. And no, according to Jason anyway, the nanny wasn’t hot.

To be honest, I think alcohol may have tainted the legitimacy of my little psychology experiment. Almost every advice-seeker was holding a cup. (It’s legal to drink outside at the Fremont Street Experience.) And nothing but a serious buzz can explain why the hell a 45-year-old woman would jeopardize her entire career by asking whether she should accept the advances of a 26-year-old man she knows from work.

It’s 2015 and being a cougar is awesome. But that was before she fleshed out all the important details: She was in town for a convention of drug counselors, and “work” was the rehab he’s enrolled in.

Obviously, I told her that sexual relations were inappropriate and that she might want to consider a line of work that doesn’t involve destroying the minds of the very people she’s hired to help.

(And if you think I may have been pranked, that’s only because you did not see the beyond-genuine look of fear on her face when I told her I was writing a story that would probably include the details of her situation.)

Only three times in three hours, I was asked what qualified me as an expert. And my response—“What qualifies anyone?”—satiated all curiosity.

“People will believe all kinds of nonsense if somebody claims to have some authority,” says psychologist Stephen Greenspan, author of Annals of Gullibility: Why We Get Duped and How to Avoid It. “You may have been particularly sympathetic or persuasive, and some people are more trusting than others.”

(Indeed, even Greenspan himself, probably the world’s foremost expert in gullibility, invested $400,000 of his own retirement savings with Bernie Madoff.)

Despite my ridiculous lack of qualifications, I like to think that most of my advice had some merit, and the three hours I spent dispensing it gave me the distinct impression of improving.

The key was listening. The overwhelming majority of people’s problems didn’t reflect an inability to identify the right answer so much as a lack of willingness to pursue it.

When Zafer Chowdhury, an 18-year-old civil engineering student at the University of Texas, asked if he could still be an engineer after taking 10 years off from college, I told him he should take that time and discover his true passion, which would pretty much be anything he’d never consider being away from for an entire decade.

Chowdhury replied with a lump-throated thank you and an offer of $5 that I had to turn down, being Free Advice Man and all.

Helping people improve their lives with no qualifications whatsoever—leave it to Dr. Phil, me, and anyone else with a cardboard sign and a table.